Miss Adela Palmer-Morewood was the daughter of William Palmer-Morewood (died 1863) and Clara née Price. She was born in or about 1848, at Ladbrook in Warwickshire, so would have been about 18 years old when this portrait was taken. On 12 December 1867 she married George Algernon Beynon Disney Hacket (born in Africa about 1845). The couple appear on several censuses. In 1891 they were living with three of their sons, two of whom were adults, at Carrington House, Osborne Road, Portsea, Hampshire. Her husband gave his profession as “Colonel and J.P.” Mrs. Hacket appears on the 1901 census, without her husband, at Morpeth Mansions, Morpeth Terrace, Westminster.

She is seen here dressed for a ball or reception, or perhaps for one of the Queen’s Drawing Rooms held regularly at Buckingham Palace.

No date is given for this sitting in the daybooks. The last date entered in volume 13, which is the last volume, was for sitting number number 17,048 which took place on 21 May 1866. Given that the studio was only seeing an average of two or three clients a day by this period, it seems Miss Palmer-Morewood would have attended the studio at the end of May or beginning of June, 1866.

An epidemic of scandal and social outrage appears to be afflicting England at the present time. There are epidemics of burglary and murder as well as epidemics of fever and small-pox. The latest trouble is a strange outbreak of crime affecting the domestic hearth and illuminating the ranks of the higher classes of society. “The Morewood affair,” a Derbyshire scandal, holds a foremost place in the social annals of the time. It is an episode of Christmas; but it is accentuated in this new year by the estreating of bail money to the extent of $20,000 bonds entered into for the appearance of four “aristocratic” prisoners who have decamped to foreign lands. The story is a curious satire upon the supposed culture and good feeling of English country families. From my own knowledge of this society I am bound to say it is a somewhat exceptional case of utter blackguardism and lawlessness.

Alfreton Hall is a pleasant mansion situated on one of the uplands overlooking the Erewash Valley, just where the green plains of Nottinghamshire rise into the wooded heights of the Peak of Derbyshire. A sweet rural valley was this stretch of the midlands intersected by one little river – Erewash – in the days before coal was discovered throughout its entire length. Now, however, colliery shafting and steam engines seam and scar its face with an erysipelas of smoke and dirt — pillars of cloud by day and fires by night. Out of these rich coal mines the Morewoods of Alfreton, a county family, have become opulent. They have “struck ile.” The father of the family died recently, and the elder brother, Mr. Charles Palmer-Morewood, a county magistrate and the Squire of Alfreton, acting as head of the family, invited a Christmas gathering of his kinsmen at the ancestral hall. His mother and his four brothers assembled there on Christmas Day. They were hospitably entertained. The yule log burned brightly. The holly bough hung over family portraits. Everything told of the great anniversary of humanity which Christendom was celebrating. The wind brought a message of Christmas bells across the valley. It was a day to renew domestic ties and to revive the happy memories of childhood and youth. All went on with peace and good-will until the mother left. Then Mr. Morewood and his four brothers adjourned to the smoking room.

There appears to have been an interval in which the merits of a greatly prized old rum, which was in a singular, antique bottle, were discussed. Suddenly, without words or warning, Squire Morewood was seized by his four brothers and thrust into the library. They locked the door inside. Then they endeavoured to dragoon him into signing a document to their pecuniary advantage. This document related to certain money mentioned in the dead father’s will, some of which, being vested in colliery interests, had not had time to be realized and paid over to them. The father left each of his sons a legacy of $100,000. Part of this patrimony the four younger brothers had received. Now they resorted to fear and force to obtain the remainder. The victim of their treachery refused to sign the document. He would not be cowed by coercion. He was told that the four brothers had cast lots to take his life. A revolver was held at his head to emphasize the threat. The elder brother resisted, and a desperate and dastardly struggle endued. It was four against one. The elder brother twice struggled to the bell and rang for help. When the butler answered the summons of his master he was dismissed by one of the brothers on some trivial errand, while the others held their victim. Finally the four miscreants left their victim on the floor senseless and bleeding. “Go into the library,” they said to one of the servants as they left the house, “you will find your master lying very drunk.” It was a sorrowful and sickening sight that met this servant’s gaze when he went into the ancestral ding salon, furnished with all that wealth could procure and taste suggest. The Squire was lying on the carpet in a pool of blood. He was entirely naked. All his clothes had been cut from off his body. He was insensible and bleeding from several wounds.

While this fracas was going on, Mrs. Morewood, the Squire’s wife, was lying in bed in the same house, her confinement having taken place only a short time previously. The four young heroes –(let me immortalize them by printing their names in full: George Herbert Palmer-Morewood, of Hallfield Gate; Alfred, Ernest Augustus, and William Louis Palmer-Morewood, of Wigwell Hall, Wirksworth)–were subsequently arrested upon warrants charging them with “unlawfully assaulting” Mr. C.R. Palmer-Morewood, Justice of the Peace, but they were liberated on bail, each in his own recognizance of $2,500, and sureties of $2,500 each, making a total sum of $20,000. When, however, the case came on for trial the defendants had absconded and the bail was estreated. The money was paid, and it is understood that it came from the pockets of the fugitives. The fact that the Police warrant was only for “common assault,” and that the aristocratic ruffians were allowed bail at all, is regarded in the neighbourhood as a serious reflection on the justice dispensed by the English unpaid magistracy. Had these civilized savages been lower in the social scale, it is said they would have been charged with a more penal offence and been offered no opportunity of liberty. Now they are reported to be laughing at the law in France or Spain. One account which reaches us from Alfreton declares they are about to embark for a cruise in the Mediterranean in the beautiful yacht of the Earl of Shrewsbury. “These four young aesthetes, their divorced and divine sister, and the lordly libertine,’ says my correspondent, “will make, no doubt, a merry crew,” and thereby hangs another story.

The young Earl of Shrewsbury not long ago was a constant visitor at the palatial residence of Capt. Mundy, a Derbyshire magnate. Mrs. Mundy is a Morewood, sister to the Alfreton brothers, of the Christmas Day outrage. Capt. Mundy thought Lord Shrewsbury to attentive to his wife, and spoke to her and to the Earl upon the subject. A slight coolness followed, and eventually an elopement. This incident “fed” the columns of society journals for some weeks, Mrs. Mundy having by general consent been added to the public portrait galleries of the photographic stores as “a professional beauty.” Derbyshire was greatly scandalized at the affair. In due course, Capt. Mundy, of Shipley Hall, obtained a divorce, and as soon as the necessary technicalities of the law are satisfied the youthful Earl of Shrewsbury will marry “the partner of his guilt.” The yacht referred to in the previous paragraph is the vessel in which Lord Shrewsbury and Mrs. Mundy are taking a semi-matrimonial cruise.

In the meantime, the disappearance of the young Morewoods from Derbyshire is causing much local satisfaction, for the practical jokes and horseplay of these surpassing representatives of England’s “gilded youth” had made them a terror to the neighbourhood. The next event in the family history is the christening by Lord Hervey (Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells and Mrs. Morewood’s father) of the little stranger whose arrival at Alfreton Hall had just preceded the outrage in which its father nearly lost his life. Says my correspondent, writing from the neighbourhood of the family seat, whither he went to collect the data for this sketch: “It might be supposed by some persons that drink was at the bottom of the outrage. But no such extenuation can be offered. I have it from the lips of the outraged gentleman (who is slowly recovering from the murderous assault) that the attack was made without any previous quarrel, and that his brothers were not intoxicated. It is, happily, a rare thing for the public to have such a glimpse into the interior of the home of an English county family. If such revelations are to become frequent some great-hearted philanthropist or earnest social reformer or enterprising missionary had better start an association for the amelioration of the aristocracy. The conversion of the cobbler and the collier has had our Christian solicitude, and the conscience of the costermonger has been carefully tended. But all the time the benighted nobility of Derbyshire appear to have been left to their own dark resources, and with results that are not encouraging for the future of their race.”

Just as I am closing this article my Derbyshire correspondent informs me that the history of the Moorewoods (sic) of Alfreton Hall is likely to come still more prominently before the world than at present. The question of rightful succession to the estates was tried in 1841 by a “claimant” whose case is not unlike in some of its details to that of the Tichborne romance. Later another claimant turned up “This person,” says a townsman of Alfreton, writing to a local newspaper, “was a man named John Williams, calling himself John William Morewood, a native of Pembroke, who has been in the army, and when at the Cape of Good Hope met with another soldier from Alfreton, who informed Williams of the history of the Alfreton Morewoods, and also the history of the Ladbroke Palmer-Morewoods. On William’s return to England he wrote from Pembroke to the late Mr. Stoppard, of Pinxton, two letters (which said letters Mr. Stoppard gave to me.) He addressed Mr. Stoppard as ‘Dear Uncle,’ and in one letter among other things, he writes,: ‘I am the son of the Rev. Henry Case Morewood and Ellen Case Morewood, and was stolen from my parents when young and sent to sea,’ when, in truth, Mrs. Case Morewood was the mother of only one child, a son, by her first husband, George Morewood, Esq., who died when a few months old. It is also true that a stout pair of boots had something to do with helping Williams not only from Alfreton Hall, but also out of Alfreton town.”

“But,” continues the same correspondent, (and he writes with an air of authority,) “the fracas which took place at Alfreton Hall at Christmas is not the only disturbance that has occurred in the Palmer-Morewood family. The late Mr. Charles Rowland Palmer-Morewood and his brother, the late Mr. Frederick William Palmer-Morewood, did not visit Alfreton at the same time, and upon an occasion of business I once had with Mr. Frederick W. Palmer-Morewood he said to me at Leamington: ‘If I live longer than my father, my brother Charles shall never have Alfreton. ‘I know of a gentleman who can trace his pedigree direct from the old Alfreton Morewoods, and is possessed of many family deeds and documents relating to the Hall estates, but he has never exercised any claim to the estates, but intends shortly to do so in a way he may be legally advised; and I think an important deed will be produced which will operate in my friend’s favour in barring the Statute of Limitations. I fancy there will be a greater surprise than that which took place in the action of Wood against Morewood in 1841. The shorthand notes of that trial are in hand, as also a private letter from the Judge, Baron Parke, dated 10 years after the trial.” We may, therefore, in the ordinary course of events, look for further revelations in the history of the county family which has so recently ruffled the aristocratic waters of high society with the shameful details of a lordly case of adultery, elopement, and divorce, and the celebration of Christmas with an attempted robbery and murder.

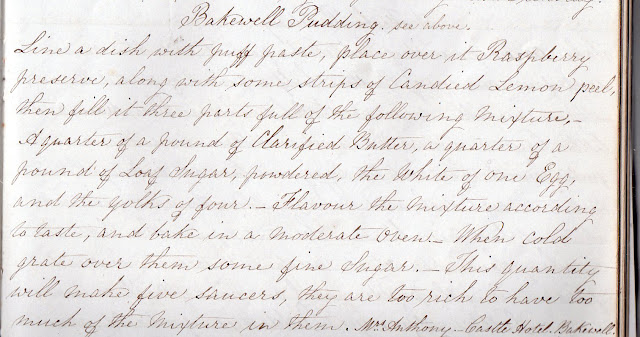

A NEWLY-DISCOVERED ancient recipe for Bakewell Pudding has served up a heated culinary conundrum about the origins of the world-famous dish. The handwritten formula was found in an old cook book compiled by Clara Palmer-Morewood, who lived in Alfreton Hall. It is clearly titled Bakewell Pudding and dated 1837 – casting doubt over local legend that the delicious dish was created by accident by Ann Greaves, the landlady of Bakewell’s Rutland Arms, about 30 years later. But Paul Hudson, her great-great-great grandson, said the newly-discovered formula bore no resemblance to his famous ancestor’s original recipe, which has been passed down through the family. The cook book, which was bought by Derbyshire County Council for a collection on the Palmer-Morewood family, contains hundreds of recipes and medicinal cures. Record Office staff came across the Bakewell Pudding recipe on page 95 and excited archives manager Sarah Chubb promptly made it for colleagues to try. “It was delicious and very easy to make,” said Sarah. She added the recipe’s discovery was a “terrifically exciting find”. Cllr Andrew Lewer, leader of the authority, said: “This will certainly raise questions about when Bakewell Pudding was invented.” However, Mr Hudson maintained his great-great-great grandmother originated the Bakewell Pudding in the Rutland Arms sometime between 1851 and 1857. Local legend states an inexperienced waitress was preparing dessert under Mrs Greaves’ orders. The flustered waitress made a mistake with the ingredients – but hotel guests loved the tasty, new sweet and shrewd Mrs Greaves made a note of the amended recipe. Mr Hudson said: “Just the other night my wife made a Bakewell Pudding using Mrs Greaves’ original recipe, which is handed down through the family on marriage. “I can promise you it tasted wonderful and bore no resemblance to the recipe in this newly-found cook book.”

This makes 10 saucers.

A Mr. Stephen Blair gave £5 for this recipe at the hotel at Bakewell about 1835. From Traditional Fare of England and Wales. (London: 1948).